Response to Hanson on Autism

Table of Contents

Part 1: The Ivory Tower

x — x i. Impetus x — x

I. The Paradox of the Successful Nerd

II. The Common Man’s Explanation

III. Hanson’s Explanation

IV. The Lobotomy Problem

V. God Help Us, Let’s Attempt to Simulate the Evolution of Human Neurotypes from First Principles

— pt 1. Social Skills: Poetry —

— pt 2. Social Skills: Pseudocode —

pt 3. Human General Intelligence: A [Relatively] Simple Genetic Story

Interlude: Forget Everything You’ve Been Told About Clinical Psychology

Part 2: The Glorious Trenches

VI. Genes, Schizophrenia, and Axon Length

VII. The Arcuate Fasciculus and the Idiot God

Interlude: Caveats to a Cortical Explanation

VIII. A Cortical Explanation

— pt 1. Apparent Effects of Congenital Blindness on Autism and Schizophrenia —

— pt 2. “Autizing-Schizophrenizing” Genes —

Part 3: A Meeting

IX: Steven Byrnes

— pt 1. Predictive Processing Latent Variables as an Explanation of Schizophrenia —

— — i. “B/A” — —

— — ii. “Q/P” — —

— pt 2. An Explanation for the Explanation: Slashed Intermediate Hops —

— — i. Theory — —

— — ii. Empirical Substantiation — —

— — iii. Consonance With Byrnes’s Other Observations — —

— pt 3. Hallucinating Schizophrenics Actually Have Better-Connected Distal Cortical Areas —

Interlude: “Radius of Simulation”

X. Scott Alexander

— pt 1. Not “Mentalizing” More, Just “Systemizing” Less —

Interlude: By “Intelligence”, I Distinctly Mean Something Other Than “IQ”

— pt 2. John Nash —

x — x ii. Appendix - The Rotator-Wordcel Axis: A Skew Axis Less Skew To Cortical Sex x — x

x — x iii. Abbreviated Bibliography x — x

Part 1: The Ivory Tower

x — x i. Impetus x — x

Robin Hanson writes,

Yes, we the socially unskilled make better social/human scientists, as we more notice when our theories deviate from behavior, both because our inhibitions are worse, and because we can reason through theories better.

I admit: I used to think this myself. As a corollary, I used to think it made sense.

But it doesn't, actually, make sense.

Not as an explanation for the "successful nerd" phenomenon. Not one that's actually useful, or general, or load-bearing, or something.

Or at least, the first part - "because our inhibitions are worse" - makes qualitative sense, but isn't useful, either clinically or as a guide for everyday behavior.

And the second part - "because we can reason through theories better" - actually doesn't make sense in the sense that it's a logical non sequitur, if we didn't already know autists could reason better, from "autists have worse social skills".*

[*Here is where, perhaps, Hanson would say that his separation of these two claims was merely rhetorical, and he really meant them as different faces of the same claim. He might say that what he really meanet, was "because our [counter-rational] inhibitions are worse [=less active, we can reason better". And I cede that to Possible Robin Hanson, that that's plausibly his position. But I observe autists both having worse inhibitions, and, on a seemingly cognitively independent level from that, having seemingly vastly improved reasoning capacity, far beyond what could be explained by removal of inhibitions alone. And if Hanson here isn't observing that same reality, and Freudian-slipping about it when he postulates two beneficial autistic symptoms, well, I am.]

I. The Paradox of the Successful Nerd

We need some explanation for the "successful nerd" phenomenon - the fact of observed experience that, in meritocracies at least, the top echelons of everything have so many obviously autistic people*.

[*Often they're not diagnosed as autistic, but, the psychiatry system being the way it is, that doesn't tell you much.]

Like many facts enmeshed in the causality common to shared experience which no one actually undersatnds, no one is quite capable of living their life around the successful-nerd phenomenon. No one living side-by-side with this strange, heterodox reality can entirely omit it from the way they explicitly think and talk about the world.

Many people never generalize any such phenomenon in their explicit understanding.

But -

Bill Gates is a teacher's pet.

Mark Zuckerberg is a cutthroat snake.

Einstein stayed inside and thought too hard and didn't play enough sports - which might have incidentally been great for physics, but wasn't, in expectation, great for the development of his character. Hence why he was such a notoriously uncharismatic public speaker.

Elon Musk isolated himself, focusing monomaniacally on his work. After many years, he now lives in the technological world of 10-years-into-the-future [excepting a blind spot where ASI is concerned], but is seemingly stuck in the socio-political world of the 1980s*.

[ A quote from Scott Alexander's review of a 2015 biography of Musk which I think nicely encapsulates the successful-nerd conundrum:

"Musk is a paradox. He spearheaded the creation of the world's most advanced rockets, which suggests that he is smart. He's the richest man on Earth, which suggests that he makes good business decisions. But we constantly see this smart, good-business-decision-making person make seemingly stupid business decisions. He picks unnecessary fights with regulators. Files junk lawsuits he can't possibly win. Abuses indispensable employees. Renames one of the most recognizable brands ever."

[And the author adds: Everyone has Musk stories. You hear them everywhere. They pile up like used paper. One of my college friends told me he once emptied a production floor of the color yellow, and I believed it. I've never heard that one anywhere else.]

“Musk creates cognitive dissonance: how can someone be so smart and so dumb at the same time? To reduce the dissonance, people have spawned a whole industry of Musk-bashing, trying to explain away each of his accomplishments: Peter Thiel gets all the credit for PayPal, Martin Eberhard gets all the credit for Tesla, NASA cash keeps SpaceX afloat, something something blood emeralds. Others try to come up with reasons he's wholly smart - a 4D chessmaster whose apparent drunken stumbles lead inexorably to victory.”

So it goes with Jobs, Turing, Edison . . . and the poetic talents too.

There exist a limited number of obvious geniuses to whom we don't have such cached narratives of accompanying disability attached.

Tao, Euler, von Neumann.

That's about it.

And not to put too fine a point on it, but yeah, they are all academics, aren't they.

Your reward for reading this linenote: the first 10 readers who can name an inventor who wasn't eccentric, I will PayPal you $20. I'm serious, by the way. This is valuable data to me, and I am expecting anyone to provide it. If I get a list of 10, I'll publish it. ]

For ten thousand successful nerds, the median English speaker will have ten thousand completely different just-so stories about why this person rose to the very top of the social network while lacking the most ordinary social skills. Or, as it's more frequently put with respect to the most successful nerds, while exclusively doing very strange forms of social engagement.

II. The Common Man’s Explanation

Others, do have some general story in their mind, that purportedly explains the successful-nerd phenomenon.

Of these, some claim it's the strict - if strange - behavioral discipline - that makes the man.

This story would go something like "The reason successful people tend to have such peculiar ways of doing things, must be that throwing social expectations out the window in favor of always doing things the same way - no matter the way - gives you unusual integrity, or efficiency, that leads to unusual success."

III. Hanson’s Explanation

An adjacent, less <<blank-slatist>> but somewhat overlapping, story, is quietly more popular among successful nerds themselves.

This story, is half of what Hanson is professing, the "because our inhibitions are worse" part.

It goes: "Some people are born with a greater-than-usual quality of <<consensus-independence>>, which excepts them from the monkey-brained social illusions that cause insanity in the rest of the human population, freeing their rational intellect for general use".

But this story fails entirely to account for a question that, once pointed out, becomes obviously much harder to answer than the question of why successful-nerds are a thing in the first place: the question of why the other 99% of the human population supposedly has a weird disease actively making them insane, such that they are all - at least in theory - one very carefully placed lobotomy away from genius*.

[ *I understand that, for a certain non-unpopular standard of what the word "genius" means, induced savants are a central example. However, for another not-unpopular standard, claims of genius are judged according to stringent requirements that the claimant prove some sufficiently prosocial effect on the world, to warrant the title. While I'm not using the word here according to the strict form of the second meaning, I hold more closely to the narrow sense of 'genius' - as brilliant social significance - than to the broader sense of 'genius' - as cognitive party trick. And I note that induced savants have never, as far as I know, qualified for the stricter meaning even in the eyes of those crowds most inclined to revere heterodox heroes. ]

IV. The Lobotomy Problem

I think Hanson, and many others, secretly imagine the real world works something like a less dramatic version of the movie Limitless: ordinary people use 10% of their brainpower, and the only thing standing between them and the intellectual world class is their Social Cognition Insanity Fetters keeping them from unlocking the other 90%.

But that doesn't invalidate the Hansonian view. It, in fact, wouldn't be logically impossible for reality to work that way.

But then the natural question is: who is building these billions of potential-geniuses, just to bind 99% of their brains dendrite and axon in Social Cognition Insanity Fetters, their whole lives long? Certainly not evolution by natural selection for inclusive genetic fitness as most people are familiar with it. That image implies a fairly meddling god.

Hanson and others would, perhaps, say: "You're one of today's lucky 10,000, Mack: humans in general have lots of social-cognitive psychological repressive mechanisms, that make us stupid by biasing us toward untrue conclusions that help us maintain our social position."

It's true that we do have lots of social-repressive mechanisms biasing us toward untrue conclusions. To understand just how deep this rabbit hole goes, I recommend reading Tooby [h/t Yudkowsky]*

Confusion often results because the term "unconscious" sometimes refers generally to anything that is outside of conscious awareness and sometimes refers to the more specific "dynamic unconscious", a special repository for mental contents that would be accessible to consciousness, except that they are actively repressed. Freud was not the first to recognize the existence of the dynamic unconscious, but he was one of the first to systematically explore and describe it (Ellenberger, 1970). Similar confusion results because "repression" describes two things: (a) the general capacity for keeping things unconscious (the meaning we will use), and (b) the more specific defense mechanism of simply "forgetting" things that are unacceptable (Erdelyi, 1985, pp. 218-225; A. Freud, 1966).

offspring may be manipulated to behave in ways that are not in their best interests (for instance, by parental sanctions against sibling conflict). Slavin observes that deception (and, therefore, self-deception) is the best strategy for the otherwise powerless child. The child's wishes that are unacceptable to the parent remain conscious, while those that would be punished are pursed unconsciously.

self-deception could increase fitness by increasing the ability to pursue selfish motives without detection.

Repression makes it easier to overlook a friend's transgression. A personal slight might have been a misunderstanding instead of a defection. Even if it was a defection, it might best be ignored in order to maintain the relationship.

The Adapted Mind

[ *and, frankly, the Sequences, if you haven't, and haven't decided not to! ]

But after one grasps the nature of these subconscious self-deceptive switches . . . the idea that simply disabling them all should vastly increase intelligence, hardly makes any more sense than before.

Now, some of you may object: "Mack! Of course it is! We just saw how it can be advantageous for evolution to make people dumber - to make it easier for them to pursue the selfish-myopic social aims that were most important in the ancestral environment, with plausible deniability - at the expense of all other uses toward which they might have put their cognition!"

And, like . . . I don't disagree, with that qualitative assessment, of what's going on with autistic ability, or more precisely with "allistic disability"*.

[ *Obligatory disclaimer: I'm not a monster who's trying to dehumanize allists because they happen to be relatively lacking in some important skills. In fact, although this happens to be kind of a radical stance to take, with respect to allism, in today's political climate, I mean it seriously: The first step to curing a disability, is being socially allowed to point out that it's a disability. Of course, autism is - as a matter of obvious fact, not moral symmetry - also a disability, beggaring its own, separate cure! ]

But with respect to Hanson's first clause - his restatement of the common wisdom that autists have relatively more resources to devote to unbiased cognition because of being less 'people-oriented' - the form that my agreement with it takes, is trivial, in the same sense that a polynomial trivially agrees with a zero that passes through its origin.

I think to frame it that way - like allists lack ability relative to autists because evolution gave wild-type humans intellectual handicaps to max out their Machiavellian social maneuvering skills - and to leave it at that, requiring no deeper paradigm shift in how we think about autism - encourages us to miss the point of what we set out to do in the first place - to solve the conundrum of the successful-nerd phenomenon. Which is a conundrum because middle managers are wondering why they aren't as successful as Bill Gates, and math majors are wondering why "normal" behavior is so difficult for them, despite how they seem so good at everything else.

State the thesis thus [ Call it the 'First Hansonian thesis', for brevity ]:

Evolution optimizes minds for something skew to perfect rationality.

Then, being born with the neurological condition of autism breaks this skew, "setting free" "man's" "natural rational capacity".

It's possible to know that - just the truth of that thesis stated above - and still not be blessed with any more workable idea of what autism vs allism are, in practice, than you had before you knew that autism existed.

It's an almost trivially true story that makes almost no reference to,

and therefore has almost no ability to predictively constrain -

- empirical social experience.

And even if you buy in to the weak predictive value of the First Hansonian Thesis . . . there's something off about it as a story to explain the following fact:

The autistic guy at your job might not be great for pull, but he's hands down the one you go to when something goes wrong.

I think the wrongness - the something off - of the First Hansonian Thesis can be gotten at like this:

If you did start reasoning from something like Hanson's state of mind about how to cognitively "unchain" allistic embryos or adults - then, like I said way earlier in this post, your most easily reachable conclusion would be that some form of behavioral or even literally neurological lobotomy was the way to go.

Which -

if you either have any intuitive sense of the real, deep, strange but consistent ways in which autists and allists tend to differ,

or any sense of the way the history of medicine tends to go -

or, as I'm about to argue, any real sense of the logic of natural selection -

- the hypothetical Lobotomy Proposal just don't sound right.

I think I have a more contentful framing of how, exactly, being born with the neurological condition of autism "sets free" "man's" "natural rational capacity", which better accesses the internals of the dichotomy, and enables us to start helping people.

V. God Help Us, Let’s Attempt to Simulate the Evolution of Human Neurotypes from First Principles

— pt 1. Motivation —

So where does my disagreement - or "skew-agreement" - start,

with the successful nerds like Hanson,

who claim their success is due to having the social-cognition "governor" taken off - and stop there?

And why do I claim that Hanson's second clause above -

- the claim that autistic excellence in reasoning, like poor inhibitions, is something we would expect just from knowing about autists' poor social skills -

- is just straight up false?

In order to reason about this problem, it will be helpful to have read https://www.readthesequences.com/An-Alien-God. Or any of the posts next to it in the Sequences. Or Dawkins's The Selfish Gene. Anything that makes it clear why it can make sense to talk about natural selection as an agent - because it is, at all, an optimization procedure - even though, no, it doesn't have conscious cognition like ours.

So armed, imagine you're evolution, operating on the early human species. Or operating on any similarly complex animal. You're just incrementally modifying your phenotypes for maximally-sized descendant-cones. That's all you care about. Looking through the keyhole of reproductive-success data, grasping the joystick of incremental genetic change [ https://www.readthesequences.com/Evolutions-Are-Stupid-But-Work-Anyway ], imagine the width of high-level phenotypic variability you can effect - way down the causal Rube Goldberg machine of embryonic development - in each generation, in an animal whose blueprint is as utterly code-rotted [ https://www.overcomingbias.com/p/why-does-software-rot.html ] as complex primates'.

Look, through that keyhole, at the place where Hanson and others are purporting the causal mechanism behind autism.

Look, through that keyhole, at the causal nexus linking personality psychology - or [Lorenzian, not Skinnerist] behavioral psychology - with cognitive psychology.

Look, in other words, from the perspective of natural selection, at the place where inborn social instinct gives way to general cognition - the kind of general cognition that's useful for solving relativity, or writing x86 assembly code: the kinds of things autistic personalities are remarkably - some would say paradoxically - good at.

You just want to maximize your phenotype's cone of descendants.

We want to test - at least simulate the test in a thought experiment - whether instinctive social ability, really trades off against general-cognitive ability. If it does, we want to know: which is more important? Under what conditions will we get more of one, versus the other?

And, critically: how can autism happen? How can some people, when the species is fully mutually interbreeding-compatible, be born with a significantly "less social", "more cognitive" phenotype?

And, medically, what kind of solutions might we expect - from a genetic perspective - might be able to give each group the advantages of the other?

Say you - or really we the Outer gods, because natural selection obviously isn't actually smart enough to step outside itself - split your world-sandbox in three.

In one world, we will set our "natural selection" equivalent, to only be able to make genetic changes that marginally improve individuals' instinctive social repertoires, for the purpose of maximizing descendants*.

In a second world, we'll set our "natural selection" to only be capable of making changes that marginally improve individuals' general-cognitive ability for the purpose of max descendants*.

[*with the assumption that, at the start, the ROI curves from evolution's perspective for each trait are equally steep - which assumption is in fact implied by modeling natural selection as a game-theoretically "rational" descendants-maximizer]

In a third world, we will impose no such restrictions. This world will serve as control, or default.

What happens?*

[*This might be a good time to openly state a disclaimer: I, Mack, have a fairly good familiarity with psychological [as opposed to medical] neuroscience, and secretly have this whole time, and it's in part this familiarity that's gonna lead, or bias, me, toward a verisimilar theory here, in a way someone without that familiarity wouldn't truly be able to replicate or follow. Sorry! I hope the part of it that I can walk through in a logical way, is illustrative anyway.]

First, the evolution that is just ratcheting its humans' instinctive social guidance systems into an optimum.

From its million-foot, million-year view -

on the one hand, all the nuance of humans' social experiences and tendencies, tossed in a blender -

and on the other, "reproductive success" -

what does this evolution see?

— pt 2. Social Skills: Poetry —

It sees Alices who failed to pick quite the right Bob, or failed to hold his attention for quite long enough, whose children failed to thrive due to genetic, or financial, disadvantage.

It sees Bobs who were insufficiently healthy, wealthy, and wise [and, it supposes, dominant], to keep and hold any Alices in the first place. It sees Bobs who missed out on marginal Alices they could have had, Bobs who "wasted" their energy on Alices who were out of fertility or not reciprocating or "disloyal", and Bobs who failed to hold the sexual fidelity of the Alices they at first won.

It sees Charlies [gender-neutral] who failed to [visibly] produce for their society, and who, along with their descendants, were quietly repaid with marginal exile into irrelevance.

It sees Dylans [gender-neutral] who* overplayed their hand in the Game of Thrones, and ended up with nothing, or underplayed it, and ended up with less than they could have. It sees Dylans who failed to attend as closely to that game as they should have, and failed to calculate out as many steps in it, as their opponents did, though they were equally cognitively capable, and lost much territory and face [and thus much progeny] to their opponents' sheer use-of-firepower in search exhaustion - and Dylans who wasted their time and attention on galaxy-brained plots for dominance, and missed their chance at moderate success.

[*Humans are pretty egalitarian foragers who generally tend toward finding hierarchy in our own societies aversive to face or contemplate - which, under approximately ancestral conditions, is generally pretty effective at keeping raw hierarchy in the political background. But the uncomfortable truth is, we do have hierarchical instincts for territory and political control. If chimp societies - whose members, by the way, lack our distaste for their hierarchy - look "feudal" to us, it is because our feudal societies are chimpish. And, from others' chimpish aggressions, evolution knows: "You can't buy security".]

It sees Eves who failed to nurture their children as much as they could have, and whose children failed to thrive, and Eves who let a belligerent child out-beg the rest and monopolize their resources, and ended up with only one family of grandchildren, where they could have had two.

It sees Frankies [gender-neutral] who, as children, were too grabby, and were summarily killed by their parents [I'm not sure how common this actually was, in forager prehistory], and Frankies who failed to grab from their parents all that they could have, which snowballed into losing out on marginal adult prosperity.

It sees Georgies [gender-neutral] who were either self-defeatingly outspoken, or self-defeatingly wilting, among their peers. And within this "Georgie" domain blossoms a whole recursively dizzying, sometimes sex- and age-specializing, tree of questions. What, exactly, is the right thing to do, and the right time to do it, to "win friends and influence people", when you don't have the time to step away from all the collabversaries who are just as smart as you are, to read or explicitly think about how to do it - you must do it all in real time, by the tick of the collective social clock?

Quoth this evolution [we imagine]:

You gotta know when to hold 'em

Know when to fold 'em

When to walk away

And when to run

You never count your money*

When you're sitting at the table

There'll be time enough to count it

When the dealin's done

[*or implicit social capital, as the case may be.]

We can see how humans have a use case for general intelligence, in this situation. But these humans are already generally intelligent. We can see how they might have a use for more general intelligence.

— pt 3. Social Skills: Pseudocode —

But that is not the lever available to this evolution. It writes only in instincts, making inhumanly dexterous watchmaker's micro-adjustments to a fuzzy, massively superposed tangle of if-then code.

#DEFINE stay_silent 0

#DEFINE speak 1

#DEFINE female 0

#DEFINE male 1

/* sorry I'm using JavaScript import syntax here;

I don't have an idiomatic way of representing C

function imports

*/

import {

function is_preparing_to_speak(Conspecific local_group_member)

function is_interrupting(Conspecific local_group_member)

} from "anterior_dorsal_visual_stream.h";

bool speak_or_stay_silent(args) {

if (args.self.social_capital <= 0) {

args.self.social_capital++;

return stay_silent;

}

if (args.interlocutor.local_social_status >=

args.self.local_social_status) {

args.self.social_capital++;

return stay_silent;

}

/* below are two for loops; under actual prod conditions these

processes and others would be running mutually

asynchronously, in parallel, with each having interrupt

conditions to abort itself and others based on the

evolution of the conversation

these would be required in real life, even though it would

look like overkill in this toy model, because the

imported lower-level function bottlenecking each for

loop is using its own specialized hardware, and can only

run one instance at a time on that hardware, but they

can be *mutually* parallelized *with each other*

I'm not actually good enough at low-level programming to

know how to represent that compactly

*/

for (int i = 0; i < args.group_present.length; i++) {

if (args.group_present.members[i].local_social_status >=

args.self.local_social_status

&&

is_preparing_to_speak(args.group_present.members[i])) {

/* we don't inc social capital here because this was a

local strategic failure of a timed decision, not made

with respect to the global asynchronous social capital

record as such, so we don't get a global-pulse-update

for respecting the async social capital record here

instead we decrement the social capital of the higher-

status group member if they started too quickly

*/

if (is_interrupting(args.group_present.members[i])) {

args.group_present.members[i].social_capital--;

}

return stay_silent;

}

}

/* another for loop; again, in prod the 2 for loops would

be running in parallel */

for (int i = 0; i < args.group_present.length; i++) {

if (args.group_present.members[i].local_social_status >=

args.self.local_social_status

&&

/* Below is a hack solution for use within a unisex low-level

* binary function; we probably want to make sure we don't

* embarrass ourselves in front of women whose status is

* higher than ours especially if we are a man, but it is

* probably also not bad to avoid this if we are a woman

* It is true that [wild-type] men and women behave

* differently, but this *has* to be *fairly* shallow, in a

* *qualitative* sense, because from our perspective as

* evolution we cannot see very well ahead of time when we

* are writing complex business logic which sex it will be

* expressed in

* and much of it can be modulated by having variables set

* to different values in men versus women, rather than

* replacing entire chunks of business logic, so evolution

* probably does use [approximations of] unisex low-level

* functions, with hacks like this in them, in real life

* incidentally, the sheer fact that all this low-level

* unisex business logic seems to tip toward loading up women

* with ~all the inhibitions sourced from the incentives of

* the male reproductive role, but not the reverse, I think

* might legit help explain why women seem so irrationally

* socially anxious

*/

args.group_present.members[i].sex == female) {

args.self.social_capital++;

return stay_silent;

}

}

*

* // etc.

*

args.self.social_capital -= 10;

return speak;

}And on and on in the encapsulated and encapsulating functions - again, in superposition with the other shadow routines running in mutual parallel on the same hardware, shifting in compute share based on our sex, life stage, dominance, and status.

To a human programmer, this mess would seem at first glance almost hopelessly difficult to iterate on in ways that predictably produce marginal reproductive success.

But the human programmer is viewing this problem, of iteratively optimizing this social-instinctive mess, with a far more serial eye, than natural selection is. Natural selection sees the glass half full. The human programmer sees that he needs to make 10,000 iterative modifications for 1 unit of inclusive genetic fitness. Natural selection sees that it can make 10,000 iterative modifications in 1 generation, and reliably see these tiny nudges mutually compound to make 1 unit of inclusive genetic fitness, in 1 generation. It does so. And this is the kind of change that legitimately makes the changed thing, more like the thing changing it.

So the humans whose instinctive social ability continues to increase while their general cognitive ability stays constant, become - per runtime compute unit - relatively more like Transformers. More like LLMs. More bafflingly efficient, relatively shallower, less legible.

— pt 4. Human General Intelligence: A [Relatively] Simple Genetic Story —

What about the humans whose general-cognitive ability gets to increase while their instinctive social ability has to stay constant?

I haven't talked at all about what general intelligence is or what human general intelligence is, or how they might be modified or amplified, on a psychological or neural level. I hope you'll take my word for it if I say: Bigger brains until you can't fit the baby's head through the birth canal anymore, and then pack the neurons. When you can't fit any more neurons without changing anything, pack the wiring layout. Increase childhood duration. Moar compute.

Higher-thinkoomph, clearer-thinking, wiser people. Same amount of social skills.

Autism clearly isn't that. Autistics universally, in one way or another per autistic person, have less social ability than wild-type humans do, not the same amount.

But, although their instinctive social aptitude is dampened, not maintained, autistic people are higher-thinkoomph, clearer-thinking, and wiser than allistic people, and they do have bigger brains, more tightly packed neurons, and [ I [weakly believe]/guess/predict ] longer neural childhoods.

Interlude: Forget Everything You’ve Been Told About Clinical Psychology

At this point, I can do nothing other than beseech you, the reader, to cross-check what I have just said, with your experience of the cluster of outstandingly successful people that our culture agrees are "weird" or "eccentric" in ways that map onto [our colloquial understanding of, not the DSM-V criteria for*] autism.

[

https://x.com/AllenFrancesMD/status/1574888166942572546

*It's an open secret - something of a motte-and-bailey, really - that the DSM does not make any professional claims about psychological realities, and considers itself to be a handbook of best clinical practices only.

My best story for how things ended up the way they did anyway, with all claims about psychology considered illegitimate unless supported by the latest edition of the DSM, goes like this:

Many professional psychologists were either marginally lazy, or not given the time and tools they needed for accurate diagnosis. They knew their diagnoses would not actually hold as much water as their patients, the patients' insurers, and government authorities were demanding; to avoid being held liable for this, they pointed the finger at the next guy up the chain, who pointed his finger at the next guy up the chain, up to the DSM. Not every psychological practitioner did this, but patients, insurers, and bureaucrats kept demanding stricter and stricter liability, and after N iterations, it was impossible not to do this as a psychological practitioner, and people who really disliked doing this stopped going into psychology [ "Scott Alexander is a psychiatrist." Yes, he started Lorien in protest! ].

The public, perceiving only that psychological professionals appeared very scared of making any claims that could not be readily supported by the DSM, erroneously concluded that the DSM was some kind of Aristotelian-corpus-esque Bible of hard-won psychological truth, and the more vindinctive laypeople ran with that assumption, and took it into their own hands to go around rebuking other laypeople who did not hew to that imagined party line. ]

Think about it. The successful-nerds - do they meet those criteria? Are they smarter, more rational, and wiser, than people who are otherwise in their reference class "should" be? Or not?

I can't extend this plea for your consideration, to less famous autistic people whom we can't use as a shared reference, with statistics or otherwise - because medical diagnosis in general is so borked as to have inevitably left you with no confidence that you can pattern-match for yourself. But note if you do or don't see a thread of continuity, from the Musks, to people of whom you've been the first to ask yourself "that's weird, is he autistic?"

Part 2: The Glorious Trenches

VI. Genes, Schizophrenia, and Axon Length

How autistic you are, is partly "down to" genes. As far as I know, what "genes for autisim" are most commonly found to do, is upregulate the proliferation of cortical neurons during fetal development, when the thalamus and cortex are filling out their ranks of neurons and innervating each other.

It appears to be the case that genes that modify the relevant developmental pathways in the opposite direction - downregulating the proliferation of fetal cortical neurons - cause schizophrenia.

When average measures of brain matter density are compared between Autistic Group A and Allistic Group B, the measures for Autistic Group A usually come out higher. When average measures of brain matter density are compared between Allistic Group B and Schizophrenic Group C, the measures for Allistic Group B usually come out higher.

When average measures of within-individual-brain median axon length [ obviously, these measures are usually fairly indirect ] are compared between Autistic Group A and Allistic Group B, the measures for Allistic Group B are usually higher [ ie, Allistic Group B usually has an [estimated] longer median axon ]. When average measures of within-individual-brain median axon length are compared between Allistic Group B and Schizophrenic Group C, the measures for Schizophrenic Group C are usually higher [ ie, Schizophrenic Group C usually has an [estimated] longer median axon ].

These two sets of findings, taken together, makes sense if you keep in mind that, when the fetal brain is wiring itself, axons don't have a destination in mind - they grow until they hit something. So as the axons grow, if they find themselves in a denser brain, they will, on average, hit something and stop growing sooner, and terminate on dendrites that are nearer to them.

Thus the usual understanding is that autistic brains have "more local" connectomes.

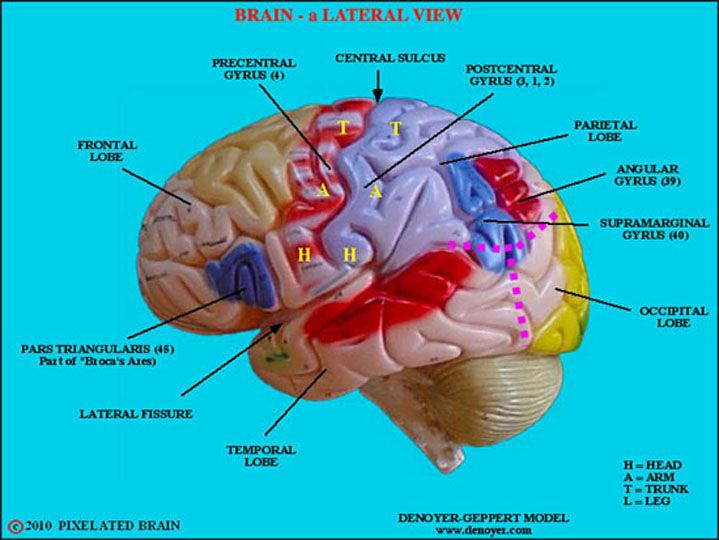

In fMRI, both autistic brains and schizophrenic brains are usually found to have weaker integration between the anterior [front, toward your forehead, involved with action-planning] parts of the "mentalizing", "social modeling" or "mirror neuron" [misnomer, but] circuit, and the posterior [back of your head, involved with perception] parts of the "mentalizing" circuit, than allistic brains. This seems to link up with how both autistics and schizophrenics seem worse than allistics at real-time mentalizing and behaving according to social expectations.

VII. The Arcuate Fasciculus and the Idiot God

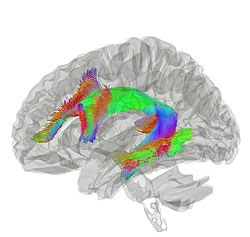

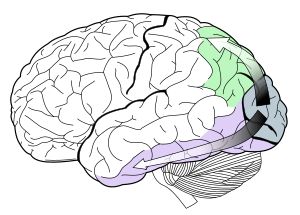

In fact there is a specific long-range white matter tract that connects the frontal regions of the human brain that model the "other", with the posterior regions of the human brain that model the "other" - the arcuate fasciculus -

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Arcuate_fasciculus

whose "scrambling" during fetal brain wiring can, I think can be blamed for the disruptions to social modeling in both schizophrenia and autism, that form these diseases' distinct characters in humans [with animal models we can induce obvious analogues of sensory and behavioral symptoms, but obviously not such distinctly human patterns as human schizophrenia's verbal hallucinations or human autism's "thing-orientedness"].

The arcuate fasciculus connects the front and back language centers [Broca's Area and Wernicke's]. Anatomically, it's largely absent in other apes. It's probably integral to a lot of the social behavior that's unique to humans.

You can see in the above image that the arcuate fasciculus is thick. It takes up a lot of space.

It's also long - all that space could be freed up if the inferior frontal gyrus [ the part where it frays out ] were simply shifted backward to be right next to the posterior temporal lobe [ the lower right scoopy part ], so they could be just as thickly connected with much more space-frugal short-range axons.

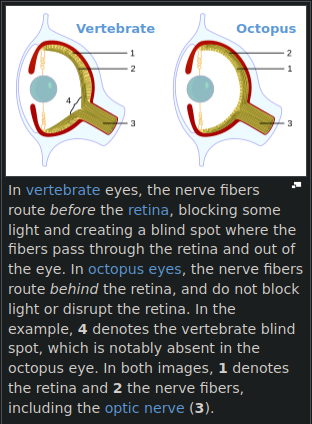

Unfortunately evolution cannot simply walk into that Mordor, any more than it can fix vertebrate eyes

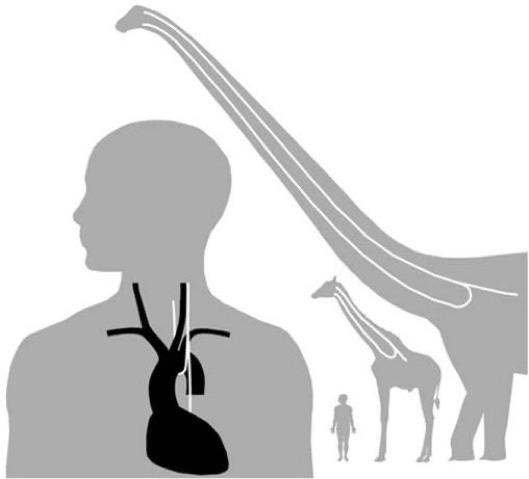

[the optic nerve sprouts out the outside of the retina instead of the inside, and gives us our "blind spot" as it loops back in] or giraffe neck nerves

[the nerve that branches to innervate the vertebrate cheek and jaw, branches behind the aorta, and could not modify the place where it forked as giraffe necks grew to make this comically wasteful]. Evolution is too dumb [especially when it comes to nerves, apparently [?]].

and so all that excruciatingly high-real-estate-value space inside the wild-type human brain [from the perspective of an evolution that is looking to marginally increase general intelligence], goes unused.

This - wiring efficiency trading off against integrity of white matter tracts essential for normal social reasoning - seems a plausible mechanism for how autism, for every unit increase in human general-cognitive ability, might, with statistical "necessity", produce a unit decrease in instinctive-social ability that's steeper along the summed ancestral-reproductive-fitness curve, thus making "autism increases intelligence" compatible with Algernon's law.

Interlude: Caveats to a Cortical Explanation

I'm actually unsure whether the frequent circadian, sex-hormonal, and serotonergic comorbidities of autism, can be explained in primarily [not entirely] cortical terms, or not. On the one hand, these things are generally understood to operate below the level of the cortex, such that just disturbing cortical development will not make a difference to them. This makes psychological sense, if you think of lizard-brain-instinct "business logic" [like the sleep cycle, sex drives, and whatever hyperpriors serotonin is setting] as generally being a thing the hypothalamus does, with the cortex [and the thalamus and the rest of the forebrain, mainly the basal ganglia and the hippocampus/amygdala] essentially being an indifferent ball of compute into which the hypothalamus's tasks are dumped. On the other hand, lots of "instinctual" drives rely on surprisingly processed inputs in the adult. Shangri-La works despite the fact that we don't know of any nuclei that would enable the brain to learn the flavor-calorie association, that are not in the olfactory[/temporal] cortex. Cortical blindness disrupting the sleep cycle is an obvious example, but I think I've heard of other cortical injuries that seemed to cause deep emotional disruption all by themselves [I'm not sure whether to count parietal/insular lesions since the mechanism in those cases may be entirely cognitive and not hormonal]. I'm not sure, though.

But most of the symptoms of autism - and schizophrenia - that we most care about, CAN be explained by a cortical model. And in diseases where we currently have no better etiological model of them than that they are "syndromes" [ie, clusters of symptoms usually found together, with no consensus etiological-level cause] - explaining most of the symptoms we most care about is important regardless of whether or not it gives us the whole picture for the development of the underlying disease. [If there even is one etiology.]

A model of schizophrenia and autism [symptoms] based primarily around a spectrum from short-range [autism], to long-range [schizophrenia], cortex-to-cortex axons, with symptoms originating primarily from disruption of major intra-cortical white matter highways - for the most transformative symptoms of these diseases in humans, primarily the arcuate fasciculus - can explain two confusing observations both Steven Byrnes and Scott Alexander have made when discussing the diametrical or spectrum hypothesis.

These are:

1. the "autizing" effect of congenital blindness, and

2. the fact that genes exist which are correlated with both autism and schizophrenia [which would seem to contradict a roughly-diametrical-spectrum model].

VIII. A Cortical Explanation

pt 1. Apparent Effects of Congenital Blindness on Autism and Schizophrenia

Explanation:

Very few people who were born blind, are diagnosed as schizophrenic.

Children who are born blind, frequently develop autistic-like symptoms, like an inclination toward repetitive play, or difficulty with processing other senses, and some degree of social aloofness [though much less social aloofness than primary autistics, as I understand it].*

[You can try to explain away the congenital-blindness-quasi-autism syndrome, on a symptom-by-symptom basis, with epicycles. Like, "well, obviously the kids have difficulty processing input from the other senses, their parents don't know how to teach them to rely on other senses in a sight-based world [not true: parents don't teach their infants how to do such basic things as rely on sight. In some non-Western cultures parents don't bother attempting to teach their kids to speak or walk, and the kids learn at least decently well]." Or, "well, obviously blind kids are socially aloof, they find it difficult to relate to sighted kids." Or, "of course blind kids play repetitively, they're stressed [repetitive play is hardly the response to stress we would a priori expect in children!]." Those who have read the Sequences will know not to.]

In light of the spectrum hypothesis, Scott has speculated on the possibility that these two things are connected, via congenital blindness having some kind of "autizing" effect. But he doesn't have a mechanism. I think I do.

If you didn't know, embryology is weird. The body has to put itself together somehow. When organisms have to do things, evolution by default gives them derpy hacks. There are genes like Sonic Hedgehog that code for morphogens - chemicals that stereotypically gradate in the embryo to mark out where it should pinch off extremities - that if you knock them out or overexpress them, the embryo will get wrong numbers of extremities. That's how weird embryology is.

[Here's an illustrative model of shrimp development for the uninitiated.]

I'm not an expert in fetal/infant/early-childhood brain wiring specifically [us being big-brained, late-developing humans, certain things that would ordinarily be embryology are in fact not done before early childhood], but one example of the way it works is:

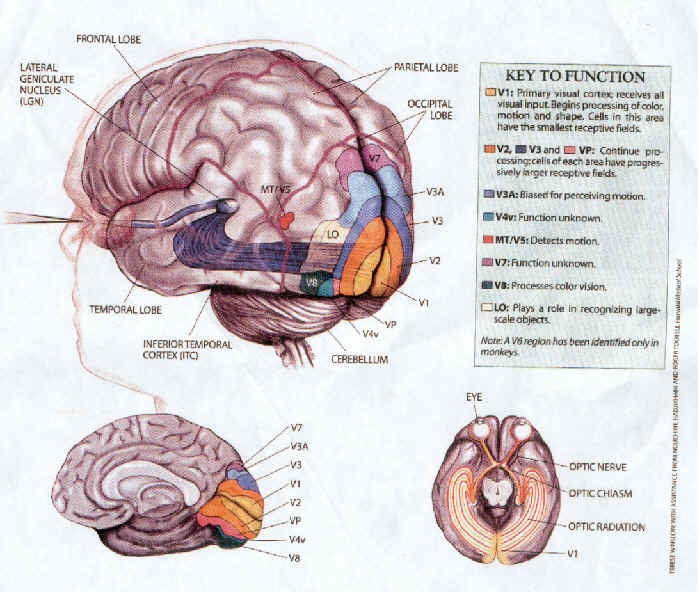

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Two-streams_hypothesis

http://www.fmri4newbies.com/retinotopic-and-early-visual-areas

If you look at detailed functional-"cytoarchitectonic" diagrams of the occipital cortex, you can visually see how backmost layers process simplest features, and then "perceptions" get passed forward to be processed by later layers that produce advanced features.

This physical gradient is formed in the fetal [and, later, infant - remember infants have very poor sight] brain by stereotyped, synchronized firing of successive occipital layers in response to "grounded-data" retinal input - i.e., light perception. If a fetus/infant does not have working retinas, their occipital cortex does not get the input it needs to do this synchronized-firing -> successive-layers-wiring dance, and their occipital cortex will not end up being wired very much like an occipital cortex is "supposed" to be wired.

Why is this autizing as opposed to schizophrenizing?

I don't know - although I think we can see that it apparently is, in "practice". My guess, for reasons that will hopefully become clear later, is that the axons that are supposed to be building up the scaffolding of cortex-to-cortex connections in the occipital lobe, are preferentially getting confused/"turned around" and terminating too soon, rather than penetrating too deeply into the brain, which "localizes" [-> "autizes"] the occipital and occipital-adjacent connectome, which leaves more intra-brain space [and white-matter-highway confusion] for the rest of the cortex to "localize" itself, as well.

But in any case we can see how congenital blindness would create an effect that penetrates pretty deep into the cortex, without having to guess about hypothetical hyperparameters or other high-level psychological factors.

— pt 2. “Autizing-Schizophrenizing” Genes —

Scott and Steven also both note that, while there is a spectrum of autizing vs schizophrenizing genes with opposite direct effects on brain development, analyses also find clusters of genes which predispose to both. How is this possible?

Say we model the genes in this orthogonal cluster, as predisposing the fetal brain toward less order in how the intra-cortical connections are built up. If you get a lot of genes in this third cluster, and your axons happen to be shorter, you'll end up with net autism. If they happen to be longer, you'll end up with net schizophrenia. Either way, your AF will be interrupted. So either way, you'll end up worse at performing social interaction in real time and coming across as "normal". And in fact, this is a shared symptom between the two diseases.

I think this makes our confusion about these "autizing-schizophrenizing" genes, go away.

Part 3: A Meeting

IX: Steven Byrnes

— pt 1. Predictive Processing Latent Variables as an Explanation of Schizophrenia —

— — i. “B/A” — —

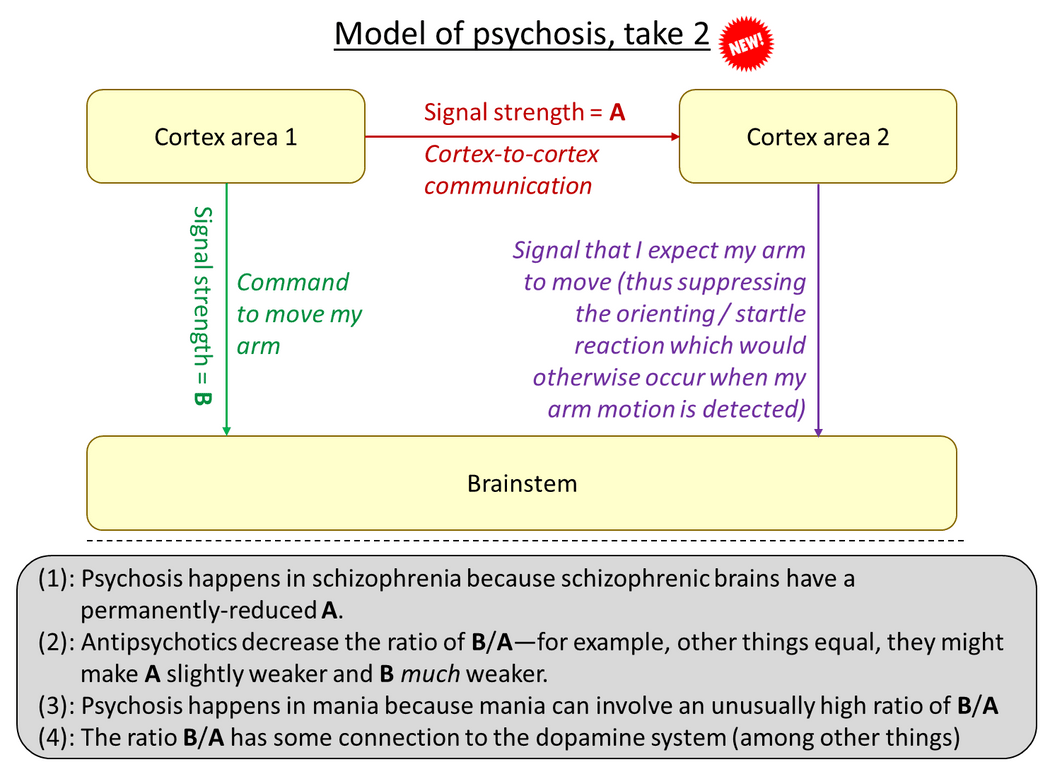

Byrnes's most up-to-date [as of Oct 14, 2024] theory of how schizophrenia works is that - in his words -

— — ii. “Q/P” — —

I've been having an extended back-and-forth discussion with Steven about my issues with this framing.

The gist is that I see no reason why the purple arrow in the diagram above, shouldn't also get assigned a letter ["C", call it], that is allowed, just as well as B, to vary independently from A, and therefore I don't see why schizophrenic symptoms should be explicable in terms of a B/A ratio, rather than a B/A/C ratio, where "A/C" is fixed for no explicable reason.

I think Steven is getting at something true and important with this theory, however. I think we can explain why blocking psychotics' dopamine receptors in particular, stops the psychosis, in cortical terms.

Quoting one of my comments:

My own view is: Antipsychotics block dopamine receptors. I think you're right that they reduce a ratio that's something like your B/A ratio. But I can't draw a simple wiring diagram about it based on any few tracts. I would call it a Q/P ratio - a ratio of "quasi-volition", based on dopamine signaling originating with the frontal cortex and basal ganglia, and perception, originating in the back half of the cortex and not relying on dopamine.

Quoting another:

"B" in your theory maps to my "quasi-volition", ie anterior cortex, or top-down cortical infrastructure.

Every other letter in your theory - the "A", "C" [...] all map to my "perception", ie posterior cortex, or bottom-up cortical infrastructure.

But why would this happen?

— pt 2. An Explanation for the Explanation: Slashed Intermediate Hops —

— — i. Theory — —

The cortex is pretty "fully connected", a neural network that would be exactly as inscrutable as GPT-4 but for years of data from EEG, physical dissection, and fMRI.

https://www.pinterest.com/pin/161355599127303681/

I think the numbers of input [sensory] and output [motor] hops are fixed by the constraints of subcortical [sensory and motor] wiring, which are relatively invariant to the effects of autism- and schizophrenia-causing genes.

I don't know exactly how this would work or to what extent it's likely dependent on the fetal brain not counting the basal ganglia [IIUC the main hub of dopaminergic signaling in the frontal lobe] as "cortical" during wiring.

Only a small percentage of the signaling that goes into making each decision is dopaminergic, and it's almost all localized "at the end of the line", in the frontal lobe.

If you vizualize the cortex as a game of "6 Degrees of Kevin Bacon", where only the final hop is dopaminergic[/pyramidal/frontal/"about control"], and then remove one or two intermediate hops, you will be "increasing the ratio of Q to P", or "B to A", or dopaminergic to non-dopaminergic signaling.

Similarly for if the cortex is 12 hops across, and the final 3 hops are dopaminergic, and you're allowed to remove any of the middle 8 hops. Etc.

If autism makes fetal axons over-proliferate and stop "too soon" for normal white-matter-tract structure, as they run into each other, and schizophrenia makes fetal axons under-proliferate and "overshoot" for normal white-matter-tract structure,

and we assume I/O is fixed and dopamine signaling is an O phenomenon,

then cortical under-proliferation could explain an increase in the "Q/P ratio", which could itself account for schizophrenic symptoms.

— — ii. Empirical Substantiation — —

I would ask of Byrnes here, to recall from above that it is a repeated result that autistic axons are longer, schizophrenic shorter.

— — iii. Consonance With Byrnes’s Other Observations — —

Then, I would say:

Recall how plausible "Intense [sensory] World" seemed as a mechanism behind autism, and a sort of "Dim [sensory] World]" in the form of schizophrenia.

In your original post, you postulated that maybe some of how top-down control of senses*, and sensory richness, seem to be just "not there" for schizophrenics, is because schizophrenic brains are less interconnected than neurotypical brains in the sense of modules being interconnected. In fact the cortex is just not very modular, or at least we don't know how to actually explain things in terms of its modules yet. It more has streams than sections, at least on a level high enough to be detectable with our current psychology experiments.

[*interesting given that we just decided schizophrenics had an overabundance of dopaminergic signaling - but then again, not all frontal connections are dopaminergic, just some of them, and many of these happen to be the ones that help determine action. I still don't understand this part.]

Deviantly few cortical hops explains a dim world for schizophrenics, and deviantly many cortical hops, an intense world for autists, without appealing to such implausibly "archipelagoed" processing modules.

— pt 3. Hallucinating Schizophrenics Actually Have Better-Connected Distal Cortical Areas —

Schizophrenic hallucinations seem an exception to the rule of schizophrenics experiencing less. Nevertheless, the arcuate fasciculus does seem to be longer in hallucinating schizophrenics, than those who do not hallucinate [and presumably longer in schizophrenics than neurotypicals [specifically what I would call "allists" when referring to the schizophrenia-allism-autism axis] ].

One might wonder whether this is because, when the arcuate gets too long, frontal areas are connected to inappropriately located sensory areas.

This is trivially part of the picture, but my theory should explain schizophrenic hallucinations the same way it proposes to explain all the other autistic and schizophrenic symptoms - as an aspect of a distributed disorder with a unified character.

I think the result of all those axons "overshooting", is that schizophrenia can be seen as a "short circuit" - when measured against wild-type or allistic white matter structure - between perception and action.

Interlude: “Radius of Simulation”

Say schizophrenics have a low number of cortical hops - lower than the rest of their body plan "expects".

This would scramble white matter tracts, including the AF, which disrupts low-level quasi-"cognitive" abilities, including instinctive social skills.

But an even deeper effect of having "too few" hops, would be that schizophrenics

- make decisions "too directly" based on perception,

and, for meta-perceptions that are themselves of events going on in the frontal lobe, eg conscious perception,

- have meta-perception that is "too directly" based on decisions.

I call this the "radius-of-simulation hypothesis", the idea being that changing your number of cortical hops, apart from determining whether your white-matter wiring can follow the "intended" tracts, also changes your "radius of simulation", or the amount of cognition that occurs between perception and action - System II metacognition included.

X. Scott Alexander

pt 1. Not “Mentalizing” More, Just “Systemizing” Less

Here, to Scott Alexander, I would say:

It's simpler to assume that it's autists, not schizophrenics, who have "overly mentalistic cognition" - because autists have "too much" cognition of all types [depending on whether it's a software hiring manager who's counting, or evolution in the ancestral environment].

While both autists and schizophrenics get [downstream disruptions in their white matter tracts] that result in fractured social-interaction abilities, it's most correct to describe autistic hyper-precision itself [which Byrnes notes is viewable as hyper-reactivity even in rat autism models] as a more-or-less strict increase in intelligence.

Autists could make schizophrenic decisions too - they just usually end up making the ones with more hops and higher discrimination, because the expected value from those is higher.* When it benefits them, autistic people don't seem particularly less religious or poetic - it's just, they can turn it off when it doesn't.

[*Of course there may also be executive function and memory-retrieval issues that come directly from having too many synapses in your brain, that are not causally downstream of having your white matter tracts disrupted.]

Schizophrenics simply cannot make autistically-discriminating decisions; they lack the neural capacity. Berne referred to schizophrenics in "Games People Play" as almost entirely lacking an Adult - the deepest cognitive mode in his theory [for those more familiar with Kahneman, think System II]. They're "more mentalizing" not because more "mentalizing cognition" is present, but because mentalizing cognition is a short cognitive circuit for humans, and in schizophrenics a lot of the cognition elaborate enough that we call it "systemizing" by contrast, is missing.

Interlude: By “Intelligence”, I Distinctly Mean Something Other Than “IQ”

This increase in intelligence for autistics, doesn't necessarily correspond to an increase in Spearmann's g, or the psychometric artifact usually taken to underlie it, "fronto-parietal integrity", because it doesn't obviously correspond to an increase in what IQ tests measure - ability to quickly complete relatively simple tasks, usually on a short clock. In case you think I'm heretically disparaging IQ tests when I describe them this way, they're intentionally designed like this, since more atomic or "elementary" cognitive tasks tend to lead to a "higher g-loading", or more correlation across sections. [Yes, IQ test designers really have gotten so turned around that they have started intentionally pessimizing their tools to provide minimal information. I can't really come up with an explanation for this, other than that no one has really tried in psychometrics since Galton.]

pt 2. John Nash

What, as Scott extremely pertinently asks, of John Nash?

Not every rule has exceptions. But maybe this one does? I won't say he didn't contribute to mathematics, and I won't say he wasn't schizophrenic.

Scott notes that his contributions were in the areas of mathematics that can be most directly modeled with "short-circuit" mentalizing cognition - not the logic of complex object patterns, but the logic of the situation between Self and Other.

He wasn't as mentally ill as most people assume - he actually chose to remain unmedicated for most of his life and nothing too bad or dramatic happened as a result [I secretly suspect this is because he had more of a handle on himself than most psychotics do], he just said a lot of weird things, freaked people out, and felt kind of crappy.

But he did contribute to mathematics. And he did apparently have pretty classic schizophrenia.

x — x ii. Appendix - The Rotator-Wordcel Axis: A Skew Axis Less Skew To Cortical Sex x — x

Scott mentions a dissociation between schizophrenic thinking and verbal thinking. While autists are sometimes called "highly verbal" because they can verbalize more explicit detail than autists, there is a possible confusion between this, and another character of cognition that might be meant by calling someone a "verbal thinker", which I think Scott is making here.

Followers of roon [who, I note, is vindicated elsewhere in this essay by the power of more cortical hops ie Moar Compute] will know of a posited demographic split between those who can play Wordle [a simple game that relies heavily on verbal long-term memory], and those who can play zigzag.io [a simple game that relies heavily on fast perception-control of [objects in] space].

Wordcels are real, and autists [as roon seemed to imply when he questioned wordcels' software vision] are not, particularly, wordcels, and actually have a slight predisposition to be better at the other thing.

Shape rotation and wordcel-ery trade off because shape rotation is pretty directly bound to dorsal-stream or early parietal real estate, while wordcel-ery is pretty directly bound to ventral-stream or early-temporal real estate.

And as you can see, they compete with each other for space since you can only fit so much inside the skull - so long as you hold degree of cortical folding, which is more or less constant with constant radius, constant.

What shape rotation vs wordcel-ery does go with, is cortical sex. Apart from the hypothalamic wiring that produces sexuality and personality, human males and females have a less dramatic divergence when it comes to cortical real estate allocation. Ciswomen have more temporal real estate, and so tend to score slightly higher on average [according to most sources] on tests of verbal ability, while cismen have more parietal real estate, and [most sources say, although this is currently more contested] tend to score slightly higher on average on tests of math ability [which presumably relies more on mental manipulation of space].

I don't think I've ever managed to get 30s on zigzag.io. I played Wordle once and oneshotted it [the word was 'skill'; it was sometime in January or February of 2022]. I think I'm autistic. This, in combination with wordcel being the cortically feminine neurotype, is why the "Extreme Male Brain" theory of autism was not very impressive to me.

x — x iii. Abbreviated Bibliography* x — x

[*Disclaimer: this list is intended to give some idea of the predecessors in this whole "try to actually explain autism" thing, who I had in mind while writing down this theory, and a few other places you might want to start if you have little familiarity with any of this stuff and want to get a better understanding of where I'm coming from. I have read more stuff than I am putting on this list; if I have failed to address the advantages of your favored explanation for either autism or schizophrenia, please comment your reasons directly instead of just saying "You missed X theory by Y author". Thanks in advance!]

Why I started asking this question / why I call it “radius”:

Identity does not mean, to such as us, what it means to other people. Anyone we can imagine, we can be; and the true difference about you, Mr. Potter, is that you have an unusually good imagination. A playwright must contain his characters, he must be larger than them in order to enact them within his mind. To an actor or spy or politician, the limit of his own diameter is the limit of who he can pretend to be, the limit of which face he may wear as a mask. But for such as you and I, anyone we can imagine, we can be, in reality and not pretense. While you imagined yourself a child, Mr. Potter, you were a child. Yet there are other existences you could support, larger existences, if you wished. Why are you so free, and so great in your circumference, when other children your age are small and constrained? Why can you imagine and become selves more adult than a mere child of a playwright should be able to compose?

High-Functioning Individuals with Autism

[ Relevant quote from Jim Sinclair:

I have an interface problem, not a core processing problem.

]

Robert Sapolsky: Schizophrenia